ONE

A CRANK, BUT ONE OF THE RIGHT KIND

There have been many Washingtons. So many Washingtons. So many more dreams and visions for the city than the one we see today. One of those dreams lasted just a decade and a half, roughly 1890 to 1906. This was the dream of an aggrandized Washington, as its creator called it. It was unimaginable in its splendor and engendered passionate support among a substantial swath of the nation’s ruling class. Ultimately, it was disastrous in its execution and in its timing.

This phantom Washington arose from the eccentric and grandiose genius of Franklin Webster Smith, whose fevered dream would soon vanish from memory along with his name.

Smith’s proposal for Washington’s Foggy Bottom neighborhood, looking west from the Ellipse to the Potomac River, 1900 (National Galleries of History and Art)

In Smith’s vision, Washington is a simulacrum of world history. The president resides in a white marble Executive Mansion towering over the city from the heights of Meridian Hill. Perched like some ancient temple, it sits atop an arch with the traffic of 16th Street running beneath it. A dozen blocks south, a vast square courtyard sprawls, two colonnaded miles around, shaded by a Florentine bell tower just shorter than the Eiffel Tower. Presidents take their oaths of office here before crowds of 100,000.

To the east, a group of mile-high obelisks looms above Judiciary Square. The goddess of the twentieth century, the modern Minerva, gazes out over the city from the central obelisk’s pinnacle. Pennsylvania Avenue runs like a Roman boulevard from the old White House to a Brandenburg Gate guarding the Capitol. Arcades shield passersby from the sun. Classical façades disguise the Old Post Office, whose gray stone tower has been dismantled and remade as a medieval German castle by the river.

A tree-lined, colonnaded Centennial Avenue bisects the Mall, leading from the Capitol to a covered Memorial Bridge, past a district of sphinxes, Egyptian temples, and three pyramids illuminated from within as if by fire. To the north are dozens of pavilions — one for each state of the Union. Between them, the walls of Toledo guard concrete reproductions of India, Assyria, Rome, Spain, and Byzantium.

A path leads through them, across a circular pool, past statues, beneath triumphal arches, and up a flight of stairs to an American Acropolis. From these heights, we see the Potomac to the west, its riverbanks adorned and its currents washing a pleasure island of hanging gardens and Chaldean ruins. In the distance, on the eastern skyline, four Roman temples, dedicated to law, government, learning, and humanity, hang above the Anacostia hills like clouds.

Franklin Webster Smith (Boston Daily Globe, Dec. 24, 1905)

This dream for a twentieth-century Washington could have been built and very nearly was. But the dream and its dreamer were creatures of the old century, not the new. Smith’s first taste of fame came in the 1860s and was less than glorious. A military contractor charged with crimes of corruption, Smith declared himself “the Dreyfus of the civil war.” After his sentence was nullified by Abraham Lincoln, he re-invented himself as an impresario of miniature world’s fairs and planner of Appalachian utopias.

He rebuilt the lost worlds of the Moors in Florida and the Romans in New York. In Washington, he recreated Egypt, Nineveh, Greece, and Persia two blocks from the White House. He envisioned the capital reborn as a vast panoramic museum of beauty and art, and his plans filled newspapers and attracted senators, millionaires, and at least one president. But the changing tastes and new politics of an infant century swept Smith aside like the empires he sought to recreate. Abruptly, he plunged into such a deep obscurity that his obituary inexplicably appeared in print three years before he actually died.

Smith’s story is that of an eccentric — a “crank,” one magazine called him, “but one of the right kind.” It is also the story of what the District of Columbia could have been. Above all, though, it is the extraordinary story of a man caught in the restless rise and abrupt demise of a visionary century.

TWO

THEY THAT DANCE MUST PAY THE FIDDLER

As the sun set on June 17, 1864. Franklin Webster Smith and his brother sat within the heavy, gray granite walls of Fort Warren, Massachusetts. Situated on a small island at the mouth of Boston Harbor, the fort was filled mostly with Confederate prisoners of war. Across the water, the country was at war. Armies were marching. Petersburg, Virginia, was under its prolonged siege. But, for Smith, there was no movement from Georges Island.

Unlike the other prisoners, Smith was a Northerner and an abolitionist. He had been present at the founding of the Massachusetts Republican Party, and just three years earlier, he and his wife, Laura, had danced at Lincoln’s inauguration. Now he sat fuming on this tiny rock, miles from land. Across the harbor, a group of Marines went to the Smiths’ place of business, broke their locks, stormed their warehouse, and stole their papers. Smith and his brother, Benjamin, sat at the commandant’s table, trapped like two caged lions.

Fort Warren, Boston, 1906 (Library of Congress)

Franklin Smith and his brother were prosperous and esteemed hardware merchants. At age 18, Smith had exhibited “One Mammoth Sample Knife and Fork” and a “Sample Card of Auger Bits” at the 1844 Exhibition for the Encouragement of Manufactures and the Mechanic Arts in Quincy and Faneuil Halls. Afterward, he partnered with his brother in their business at 32 Dock Square.

But Benjamin and Franklin — as their names might suggest — were also men of society. Their father, also Benjamin, had been the city’s port warden and leader of its Freemasons. He had been involved in the construction of the Bunker Hill Monument, whose dedication commemorated the battle that occurred 89 years before to the day. Their mother, Mary, was the daughter of a famed Provincetown sea captain.

But in June 1864, they were prisoners, albeit prisoners with friends. After their bail was set at $500,000 (nearly $10,000,000 in 2018 dollars), the people of Boston raised double that amount within a day. The Navy took $20,000 and let the two brothers return home.

Nearly two months passed before the charges were revealed. The Navy accused the brothers of an irregularity of a few hundred dollars, but it was well known that their true crime had been to provoke the Department of the Navy at wartime.

The incident began two years earlier, in 1862, when Smith Brothers & Co. entered into a series of contracts to provide the Navy with white oak staves, iron, beeswax, coal shovels, wrenches, thermometers, cooking utensils, muriatic and sulphuric acid, and antimony in support of the Union effort. Franklin Smith observed fraud and corruption in the Navy contracting process and sent letters and printed pamphlets to expose it. Of this period, he later wrote, “War is merciless. Its miseries do not culminate in the aggregate slaughter of armies. Its demoralization awakens avarice, deadens sympathy, hardens conscience and lowers the standard of public morality.”

His pamphlet made its way to Congress, where an investigation followed. “I have been summoned before the Select Committee of the Senate for investigating frauds in naval supplies,” one witness wrote to another, “and if the wool don’t fly it won’t be my fault. Norton, the Navy Agent, has complained that I have interfered with his business; he and his friend Smith are dead cocks in the pit. We have got a sure thing on them in the tin business. They that dance must pay the fiddler.”

After their arrest, and throughout the ensuing trial before a Navy kangaroo court, Boston and the entire Massachusetts congressional delegation rallied in support of the brothers’ good names. In March 1865, after they were convicted, Senator Charles Sumner traveled late at night through a thunderstorm and flooding in the streets of Washington to persuade the President to set aside the verdict. In the early hours of March 18, Lincoln reached his verdict. The brothers were freed and the judgment and sentence against them declared null.

Lincoln’s nullification of the judgment against the Smith Brothers, March 18, 1865 (Library of Congress)

A month later, Lincoln was dead. Smith presided at a memorial service at Boston’s Tremont Hall. To America, the episode of the Smith Brothers became a celebrated example of the Solomonic wisdom of the slain leader. But Franklin Smith, who later published his own account of the conspiracy against him, was bitter and declared himself “the Dreyfus of the civil war.” The episode imparted a sting, a paranoia, and a distaste for contemporary commerce that would never leave him.

After the war, Smith became treasurer of the Atlantic Works, a shipbuilding company, and a member of Boston’s Board of Trade. But in place of industry, he began to look instead to a dream of art and beauty that had grown within him since 1851 — a way, perhaps, to cleanse his reputation of the stain of corruption.

THREE

A BAZAAR OF THE NATIONS

Just before eight in the evening on April 29, 1873, Franklin Webster Smith, Chairman of the Executive Committee of the Bazaar of the Nations, welcomed his guests to the Music Hall on Winter Street, Boston. Inside the hall stood a city street lined with a dozen full-scale replicas of buildings from around the world: Jerusalem’s Damascus Gate, a three-story Russian house made of buff stone and malachite, a four-story French house with a red-and-blue Mansard roof, a palace by the Grand Canal in Venice, an Old English house, a German house, a Turkish house colored red and green with a 60-foot minaret, a Swiss chalet, and a Chinese pavilion painted yellow and vermilion.

“This scene presents an illustration,” Smith told his guests on the Bazaar’s opening night, “of the Divine declaration that God ‘hat made of one blood, of all nations of man, for to dwell on the face of the earth.” A Bavarian band led the crowd in hymn. A clergyman offered a prayer. A series of addresses followed in Russian, Swedish, French, Gaelic, German, Arabic, and Hawaiian. A Boston tea merchant delivered an address in Chinese. Four Arab runners led a procession around the Music Hall. A Bavarian band followed, dressed in red and gold. Two Swiss guards, two gold-helmeted bodyguards of the French emperor, and steel-helmeted flag-bearers in chain mail followed behind. Two men from China, a Syrian missionary, an American dressed as a Bedouin, German students, and Turkish soldiers picked up the rear. A muezzin cried out from the top of the minaret.

Bazaar of the Nations at Music Hall, 1873 (National Galleries of History and Art)

The Bazaar was the echo of a meeting twenty-two years earlier, in 1851, when a reformed sea captain “who, in his roving life, had realized intensely the temptation to which young men in the thronging streets of modern cities are exposed,” called 32 friends to Boston’s Central Church — among them Franklin Smith. Thus was born the Boston chapter of the YMCA — the first in America.

Within a few years, Smith had become the chapter’s president, and, when it faced financial troubles, he became its savior. In 1858, he proposed and oversaw a profitable Christmas fair with two full-scale rooms from Benjamin Franklin’s birthplace, men and women in early eighteenth-century costumes singing period songs, and a 50-foot-tall, nine-tiered Chinese pagoda.

Now, in 1873, behind his puffy greying mutton chops, the curious, bright-eyed Smith did it again. When the chapter again faced financial troubles, he retreated into his study and emerged with an enormous canvas showing the Music Hall transformed into a Bazaar of the Nations. Six years earlier, the world’s fair in Paris had featured dozens of national pavilions: an ancient Egyptian temple, the tent of the Moroccan Emperor, a Turkish pavilion covered with colorful tiles, an Ottoman mosque, the palaces of Persepolis, a village of Russian cottages, and a Siamese elephant pavilion. Smith proposed a new fundraising event. The YMCA would resurrect the Paris fair in Boston, recreating buildings from Europe, North Africa, the Middle East, and Asia within the Music Hall. The result was unlike anything Boston had ever seen.

Christmas Fair at Music Hall, Boston, 1858 (National Galleries of History and Art)

Throughout his long life, Smith was consumed by varied interests. He was a businessman, but also found himself in religious organizations like the YMCA, the American Tract Society, and the Young Men’s Society for the Evangelization of Italy. He found himself in politics, too. But above all else, Smith was a traveler. On March 24, 1851, 24 years of age, he stood before a notary public to apply for his first passport. (The pre-photographic document described him as 5 feet 7 inches tall, high forehead, blue eyes, short nose, large mouth, square chin, light brown hair, light complexion, and oval face.) He was bound for London, the site of the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, the world’s first world’s fair.

If the Industrial Revolution was born in the mill towns and factories, its debut came on May 1, 1851. Under cloudy skies, the 32-year-old Queen Victoria, herself entranced by technology and history, entered a 100,000-square-foot greenhouse, called the Crystal Palace, that stood at the center of Hyde Park. Within, tens of thousands had gathered to watch her process before them, through stands of flowers and tropical plants, past fountains and classic statuary, to a velvet-covered Indian-style throne beneath a 30-foot canopy of gauzy silk. Women waved their handkerchiefs, and men threw their hats in the air.

For a moment, the clouds parted, and the sun emerged shining through the panes of the great greenhouse. The combined choirs of St. Paul’s and Westminster Abbey erupted in the Hallelujah Chorus. Prince Albert, who had organized the fair with Henry Cole, the inventor of the Christmas card, addressed the crowd. The Archbishop of Canterbury followed. As a pipe organ and trumpets sang out, Victoria declared the fair open. As she and her party exited, her subjects, and the inhabitants of every other realm, were left to gaze upon the extravagance of a new industrial era.

Opening of the Great Exhibition, 1851 (Dickinsons’ Comprehensive Pictures of the Great Exhibition of 1851)

Everyone who saw the Great Exhibition was awestruck. To Charlotte Brontë, it seemed as if “only magic could have gathered this mass of wealth from all the ends of the earth.” Dickens was “used up” by it, writing “there’s too much…so many things bewildered me.” Amid the pathways and stalls of the Crystal Palace, 15,000 exhibitors introduced the world to steam engines, locomotive engines with wheels eight feet in diameter, new types of locks and firearms, envelope-making machines, button-making machines, calculators, coffee roasters, biscuit-making machines, dehydrated beef “meat biscuits,” and elongating galoshes. It was here the world first discovered the telegraph, vulcanized rubber, the voting machine, the fax machine, and the original public toilets, called “George Jennings’s Monkey Closets.”

But, like a rebuke to the promise of technology, the Crystal Palace itself was adorned with more sensory splendors. Beneath fanciful Moorish ironwork, its pillars were hung with red, blue, and yellow shawls and canopies. Classical statues of Roman, Biblical, Renaissance, and Shakespearean characters lined a long central avenue punctuated by a thirty-foot fountain of cut crystal. A 793-carat diamond from Punjab, called the Koh-i-Noor, or Mountain of Light, scattered sunbeams like starbursts. “I think the impression produced on you when you get inside is one of bewilderment,” Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, the future Lewis Carroll, wrote to his sister. “It looks like a fairyland.”

Perhaps the most striking thing about the Industrial Revolution was the nostalgia it bred for the pre-industrial world. In a world of burning rivers, clockwork regularity, and anonymity, there was comfort in the romance of earlier times, in the idea of beauty for beauty’s sake. To Smith, the fair was a first taste of a vast world beyond Boston and a time beyond his own. He saw exhibits from every nation: an Indian elephant and palanquin, a Ceylonese temple, Spanish furniture adorned with gold and gemstones from the Andes, Persian costumes, an Arabian tent, and an opium-smuggling boat from China.

Afterward, Smith traveled through England, Germany, and Italy. “Returning home,” he wrote much later, “impressions of places and objects revived with covetous yearnings for their more substantial resemblance than the poor pictures of the time.” In the days before widespread photography, he built models of the ancient places he had seen — York and Holyrood, Wittenberg and Wartburg, Rome — and those he could only imagine, like Jerusalem and China.

Smith’s models of Porta Maggiore and Micklegate Bar, 1850s (National Galleries of History and Art)

In a time when many or most people barely ventured a day’s journey from their homes, Smith traveled abroad nearly two dozen times, through the medieval cities and Roman ruins of Europe, the Moorish palaces of Spain and Morocco, the pyramids and temples of North Africa, and the souks and mosques of the Middle East. At home, he had his models to remind him of the world beyond Boston. He later recounted, “miniature models only stimulated an impatience for architectural reproduction on a full scale.” That was his dream and ambition.

After 1851, Smith’s models soon grew full-size to become the 1858 fair, and later the far more extravagant 1873 Bazaar of the Nations. Newspapers as far away as Hawaii described the German choir, the ode to the Sultan sung in Arabic from the top of the Damascus Gate, the Oriental wedding procession wending through the Music Hall from the Turkish House to the Syrian Bazaar. “You may eat olla podrida in an Italian restaurant, or chaff the garçon in a French one,” one paper wrote. “The Highlander will blaw his blast on this side wi’ his bagpipes, and, on the other, the pig-tailed Celestial will make Music Hall dolors with the melody of the plaintive tumtum.”

The Bazaar of the Nations was also a financial success, and the idea spread. In Chicago, men like Marshall Field and Cyrus McCormick were busy planning the city’s first great fair, the Inter-State Industrial Exposition, to show off the city’s reconstruction since the devastating fire two years earlier. A magnificent racetrack-shaped pavilion was rising above the train tracks along the lakeshore where the Art Institute now stands. More than 500 exhibits filled the pavilion. A fine arts salon, featuring the sprawling landscape paintings of Albert Bierstadt, showcased Chicago’s rise from frontier to cultured metropolis. Soon, men and women like Field, McCormick, and their wives, joined Smith to plan an even grander Bazaar of the Nations to accompany the Exposition over the Christmas season.

But if Smith’s life is one of bold fantasies, it is also one of thwarted aspirations. In September 1873, just as enthusiasm was building for an enlarged Bazaar of the Nations, bank after bank began to fail. On September 20, the New York Stock Exchange closed for ten days. The railroads declared bankruptcy, and factories laid off their workers. As the depression deepened, the Chicago merchants lobbied against the Bazaar. Its competition would ruin them during the holiday shopping season, they argued. The Chicago YMCA initially argued the Bazaar would stimulate commerce but ultimately agreed to postpone the event. Imitators sprang up in Massachusetts, Newark, and Philadelphia, but the great Chicago Bazaar never came to be.

Participants at the Bazaar of the Nations, Boston, 1873 (B.Y.M.C.A. Bazaar of the Nations: Reports and Acknowledgments)

Though the Chicago Bazaar venture ended in failure, Smith never forgot the success of the Boston Bazaar. The city had turned out in droves to enjoy its first clear view of a world far beyond the city’s horizons. Its citizens attended Arab banquets and Turkish banquets and a “Chinese Meal with Chopsticks.” Costumed dervishes whirled past Bedouin and Scottish sword dances and a Highland fling. Boston Brahmins donned costumes, imitating Parisian fishmongers, Arab letter-writers, French limonadiers, Bedouin booksellers, and Russian coachmen. They sold Roman baskets, Greek marbles, and other trinkets Smith had bought in Europe to fairgoers from beneath broad arcades. In a world of commerce and industry that seemed increasingly colorless and unforgiving, Smith saw how the romance and curiosity of other times and places kindled excitement. The Panic of 1873 may have killed the Chicago Bazaar, but the idea of the Bazaar would pale beside the dreamscapes billowing in Smith’s mind.

FOUR

THE HARD TIMES

On October 5, 1880, a crowd of a few hundred gathered in a wild corner of Tennessee’s Cumberland Plateau to christen a new settlement. The morning began overcast and dreary, with heavy clouds hung precariously and foreboding over darkened forests. It had stormed, and “all visible nature seemed dripping with the rains of the past twenty-four hours.” It seemed an inauspicious beginning, but, by late morning the clouds parted, the sun came out, and “a pleasant breeze rippled the forest leaves.” Out of the wilderness of the plateau, they had platted a village and erected a cluster of Victorian buildings — homes, a boarding house, a church, a school — as a haven from a corrupt and dehumanizing world outside.

Now they gathered to inaugurate their experiment. The town’s two founders spoke. The Englishman was the acclaimed novelist, Thomas Hughes. Hughes spoke of caring for “this lovely corner of God’s earth which has been instrusted [sic] to us,” and of treating it “loving and reverently.” The American, Franklin Webster Smith, spoke of agricultural techniques to ensure the town’s prosperity. He spoke of “mixed farming” and promise to himself prepare an illustrated handbook to guide the townspeople in this technique. Given the freshness of the air and the cleanliness of the streams that ran past the town, he spoke also of building a sanitarium. A poem, “Waking Wilderness,” was recited. With the ceremony concluded, the halcyon hamlet of Rugby was born.

Map of Rugby Tennessee, 1885 (The Rugby Handbook)

If the Panic of 1873 killed the Chicago Bazaar, it gave birth to Rugby. In 1877, as President Hayes sent in federal troops to quell striking railroad workers, Smith published a series of four articles in the Boston Daily Advertiser, together calling them The Hard Times: Agricultural Development the True Remedy. “The only remedy for existing distress,” he wrote, “is a redistribution of labor; its inversion from trade and manufacture, where in surplus, to tillage of the Earth, the basis of all industries and the primary source of all wealth.” Catching the era’s agrarian, populist fever, he argued America’s depression was the result of paper money, overproduction, and the mechanization of labor. The solution, he proposed, was to move the poor from the Eastern cities to the wide-open spaces of the fertile West.

After his experience during the Civil War, Smith must have felt a kinship with those displaced by commerce and industry. He always viewed with skepticism those who didn’t share their riches with others. He devised a scheme for parceling out tracts of land, parks, and schools to settlers who agreed to temperance and established the Board of Aid to Land-Ownership to manage it. The plan was for a group of wealthy New Englanders to purchase a large plot of uninhabited land. They would divide it amongst themselves, equip would-be settlers with money, farm implements, seeds, and provisions, charge them little interest, and urge them westward to a better future.

This was an era of contrasts, an era of tension between a new modernity and the way of life that preceded it. Within a lifetime, America had grown from an agrarian nation to an industrial one. Idealists established atavistic utopias: Oneida, Brook Farm, Vineland, the Shaker town of Hancock, and the prohibitionist, agricultural cooperative of Greeley, Colorado. Smith imagined still more new, beautiful, healthful towns away from the squalor of the industrial East. These places seemed to shun the grit, the ugliness, and the anonymity of manufacturing in favor of the pastoral beauty and community of agriculture.

“He had a life-time sorrow and a life-time dream,” the editor of the Wichita Daily Eagle wrote in a 1908 obituary for Smith. “His sorrow was that commercial vandalism was wiping out the great living pages of history. His dream was to preserve them.” If not for the glaring error that Smith, in fact, died three years later, in October 1911, the obituary is so perfectly written that it might otherwise have been written by his own hand. This tension defined him, eventually dominating his life and driving a wedge between him and his wife, Laura, and children, George and Nina, but it was hardly unique to him.

Egyptian Court, Crystal Palace, Sydenham, 1854 (Views of the Crystal Palace and Park, Sydenham)

The Great Exhibition of 1851 had awakened a craze for all things pre-industrial. In an era entranced by Egyptology and Orientalism, bestselling books included Washington Irving’s Tales of the Alhambra, Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s The Last Days of Pompeii, and the sagas of Sir Walter Scott. The Romantic poets wrote of Ozymandias buried beneath the sands and the lover Don Juan darting through moonlit alleys.

The greatest manifestation of this obsession came in 1854, when Queen Victoria christened a second Crystal Palace at Sydenham, far larger and more ornate than its predecessor. Beneath its glass roof were a series of Fine Arts Courts. An avenue of sphinxes led through a temple gate into a court of lotus-capped columns, statues of pharaohs, hieroglyphics, and carvings of asps and vultures. Through the Court of Amunsthph, through a colonnade, through the darkened tomb of Beni Hassan, through Karnak, sat the great seated figures of Abu Simbel. Beside the Egyptian Court were a Greek agora and the outer wall of the Colosseum.

Through the arched, stone gate of the Alhambra sat the Court of Lions, the Hall of Justice, and the Hall of the Abencerrages with its stalactite ceiling. Four enormous white bulls with the bearded heads of men guarded the vividly painted Assyrian Court. Other spaces reproduced the cloisters of Byzantine and Romanesque Europe, the castles and cathedrals of Medieval Germany, England, France, and Italy, and the Renaissance, a reawakening of European culture not unlike that of the nineteenth century.

Assyrian Court, Crystal Palace, Sydenham, 1854 (Views of the Crystal Palace and Park, Sydenham)

These exhibits inspired Smith’s grandest schemes, but they were schemes better suited for times of prosperity. During the 1870s, as banks failed, businesses closed, and unemployment surged, there was little appetite for the recreation of distant and ancient lands. Smith turned instead to his bucolic utopias.

In the winter of early 1878, Smith traveled more than 7,500 miles through the lonelier places of the West and South to find the site for his colony. He rode private trains along railroads through the prairies and empty quarters of Nebraska and Kansas. He traveled through Iowa and Arkansas. While he was in Texas, the Times-Picayune eagerly promoted Louisiana. “If the rich men of the United States desire to prevent the spread of communism and agrarianism,” the paper wrote (four decades before the Russian Revolution), “they must follow the example of the Boston capitalists, who lead off in this patriotic and benevolent enterprise.”

In mid-May, a Tennessee official wrote to Smith of the Cumberland Plateau. “With no rent to pay, no fuel to buy, no severe weather to provide against in the way of clothing,” he wrote, “with health, a sunny sky, a bracing atmosphere, the cost of living here will be reduced to a minimum. Let your people come. They will be welcomed with a heartiness characteristic of Tennesseeans,” no matter that, barely 15 years after Appomattox, Smith intended to relocate Northerners to the rural South.

Smith visited the streams and woodlands of the Cumberland plateau and then passed through Nashville. “Mr. Smith is a polished and courtly gentleman of the old school — a man of enlarged business experience, ripe culture and extensive travel,” the city’s newspaper reported. “On the subject of the Cumberland Table-land he is almost an enthusiast.” The paper lent Smith’s movement its “heartiest sympathies,” and, in the summer of 1879, his Board purchased 60,000 wooded acres 70 miles northwest of Knoxville, where two streams came together to form the South Fork of the Cumberland River, 70 miles northwest of Knoxville.

The spot was, one paper wrote, “surpassingly beautiful.” There, the Board planned to build a small settlement surrounded by nature, without fences or alcohol. Hardworking fathers currently “obliged to live in back streets, or alleys; in filthy tenements surrounded by unhealthy atmosphere” would spend their days together planting fruits, caring for livestock, felling trees, and harvesting vegetables. Their children would be removed from “‘an atmosphere of drunkenness’ to pure air and a green-sward.”

Farmers at Rugby, Tennessee (The Rugby Handbook)

Meanwhile, a group of English businessmen learned of the negotiations. Concerned for their own sons, displaced from land ownership by primogeniture and agriculture work by caste, they turned to Thomas Hughes, a politician, labor activist, and author who had discovered “in America sons can be appropriately placed.” One of his sons bought and sold cattle in Texas. The Englishmen banded together and approached Smith. They and Smith’s Board formed a new organization and based it in London.

By October 1880, twenty families had settled at Rugby, half of them American, the other half British. Fifty more families, mostly English, were expected over the winter. They called their settlement “Rugby,” after the setting of co-founder Hughes’s blockbuster novel Tom Brown’s School Days. On a ridge above where the two streams met, they laid out Central Avenue. They erected homes and cottages, a church, gardens, a free library with more than 6000 volumes, three general stores, a drug store, and a hotel called the Tabard after Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. A deer park sat beside it. They opened a weekly newspaper, installed a telephone, and prohibited “the traffic in intoxicating liquors.” They played lawn tennis and listened to concerts of the cornet band. Children played on swings, and everyone went for walks where “the novel scenes of primeval forest life, touched by distant peeps of mountain ranges, and the near tumbling, or smooth-flowing streams, all give an ever-recreative strength to mind and body.”

Rugby, Tennessee, 2010 (Wikimedia Commons/Brian Stansberry)

But Smith also envisioned a new purpose for Rugby. Visitors were expected that summer, and plans were drawn up for a a sanitarium that would become “an attractive resort for invalids.” He surveyed bridle trails into the scenic gorges. He imagined other activities for the hordes of Eastern urbanites he anticipated would flock to the healthful mountain air. Mass tourism was a relatively recent innovation, made possible only by the leisure time and transportation infrastructure of the Industrial Revolution. Like the Bazaar of the Nations, it offered the possibility of both an escape from and a lesson for the modern world.

But where Smith saw potential, Hughes cared only for utopia. The two ultimately parted ways. Smith left for Europe, and Rugby remained a mostly English experiment. The town survived briefly, reaching a peak population of 300, but soon fell into obscurity. By 1900, after fires and financial disasters, it was mostly deserted. While Appalachian resorts like the Greenbrier and Homestead continue to thrive today, only a few Victorian buildings remain at Rugby today, like startled rabbits amid the upland forests, to mark its vision, its promise, and its ultimate failure.

FIVE

THE AMERICAN RIVIERA, THE NEWPORT OF THE SOUTH

William Drysdale was a traveler, a handsome enough fellow, with an immaculately groomed mustache, who would go into the world sometimes to write. He published travelogues, like In Sunny Lands: Out-Door Life in Nassau and Cuba, and novels of romance and adventure, like The Princess of Montserrat: A Strange Narrative of Adventure and Peril on Land and Sea. He wrote letters for the New York Times, too, reporting from distant lands, signing them, simply, “W. D.”

In January 1892, Drysdale again left his wife and son in New York, bound for “the realm of eternal Summer, 1,400 miles down the coast, where bananas are ripening for us, and gorgeous birds singing in pleased anticipation of our arrival.” He visited Tampa first, then headed for St. Augustine. Disembarking from the train, he wandered down King Street toward town and came upon something fantastical: among the marshes and swamps of Florida, a Moorish castle constructed of concrete with keyhole windows, crenellations, and wooden balconies painted crimson and bright yellow. Vines roamed free across its surfaces. Over its front door, an inscription read in Arabic, “there is no conqueror but God,” the motto of the Emirs of Granada. The strange home was called the Villa Zorayda, after a princess in Washington Irving’s Tales of the Alhambra. It was one of the great curiosities of this resort town by the sea.

Drysdale yanked at the villa’s bell. An “Arab in dress coat and white tie” appeared at the door to welcome him. Inside, he was ushered into a courtyard lit by sun shining through primary-colored glass. Thirty-six concrete arches covered in Moorish tracery surrounded him, and the floors beneath his feet were paved with Spanish tiles. Divans and plush pillows situated among the vases and banana plants beckoned. The home’s owner, Franklin Webster Smith, sat awhile with Drysdale in this “corner of Morocco,” on a divan amid the banana plants, speaking of ancient architecture and the great living pages of history revived.

Stereograph of Villa Zorayda, 1885 (New York Public Library)

In the 1880s, Florida was still mostly wild swampland and sandy pine barrens. The state was only just beginning to open up to widespread settlement and, with its warmer climate, tourism. Wealthy Northeasterners were just beginning to flock to sleepy, subtropical St. Augustine. The town had a certain romance — crumbling old buildings, narrow streets, an old coral fort, tales of conquistadors, and memories of Spain — that attracted the likes of architect James Renwick (designer of Washington’s Smithsonian and New York’s St. Patrick’s Cathedral) and tobacco baron George L. Lorillard (maker of Newport and other cigarettes). Others followed. They sought warm water, blue skies, and winter sun. Amid the palms and fruit groves, they built a yacht club and two dozen hotels.

After abandoning Rugby, Smith traveled through Europe. When he returned to America, with visions of Moorish Spain swirling in his head, he ventured south to Florida. There, he found St. Augustine, the Ancient City, founded in 1565. In 1883, he built his Alhambra there, near the swampland just west of town. The home quickly became an attraction, and Smith threw open its red and yellow doors to give lectures on Moorish architecture.

Courtyard of the Villa Zorayda, 1890s (National Galleries of History and Art)

Two years later, another dreamer, Henry Flagler, came to St. Augustine. Rockefeller’s partner in Standard Oil, Flagler was one of the wealthiest men in the world. Over the next decades, he would build a railroad racing all the way down Florida’s east coast and across the sea to Key West. Flagler fell in love with St. Augustine, and he and Smith became friends. They shared a vision for a new kind of resort. Smith and a local doctor quietly bought up properties around the Villa Zorayda for a trio of hotels they would build with an ancient material Smith had rediscovered in Switzerland: concrete. They worked together for a while until Flagler wrote to Smith, “the scheme has outgrown my original ideas.” They remained friends but worked apart.

As years went by, three enormous concrete structures rose around a grassy, central plaza. They were the first concrete buildings in Florida and nearly the first in America. Flagler built the Spanish-style Ponce de Leon Hotel and the more modest, but still extravagant, Hotel Alcazar with its steam baths, swimming pool, and casino. Smith built his own hotel, the Moorish-style Casa Monica. They called the grassy plaza between them the Alameda.

Together, the complex formed the center of Florida’s first purpose-built wonderland: a manufactured Spain. “There is a newness about St. George street,” wrote one reporter, “which seems out of keeping with the newspaper and magazine description of the ancient city. Everything old has a sort of preserved appearance, as if an old shingle, when it becomes too old, is replaced by a shingle also old, but not quite so old, and it is in this way that the buildings are so wonderfully well preserved. In other words, the city is ancient ‘for revenue only.’”

Old St. Augustine, about 1887 (Florida, the American Riveria; St. Augustine, the Winter Newport)

As their projects neared completion, Flagler and Smith published a pamphlet advertising their projects. They boasted of eternally warm breezes, impossibly blue skies, and year-round greenery. “Verbenas carpet the earth with matchless colors,” they wrote, “and when the heavens, which are always blue, are bespangled with stars, the air is filled with showers of fire-flies, lighting up the dark cypress and ancient cedars, hung with funereal mosses, and presenting a weird picture of beauty which pen fails to describe.”

They spoke of “Florida, the American Italy,” “Florida, the American Riviera,” and “St. Augustine, the Winter Newport.” Their expansive ambitions included “throwing off this bondage of winter” and following in the footsteps of old Spanish conquistadors questing for the Fountain of Youth. “We claim that the day-dreams of the sixteenth century have become the realization of the nineteenth,” they bragged, “and that the true Elixir of Life is to be found in this incomparable treasury of balmy airs, golden sunshine and health-giving waters.”

When the Ponce de Leon finally opened on January 13, 1888, it was an immediate attraction. Newspapers carried descriptions of the building across the country. They described its outer wall, a mile in length, of blue-gray concrete and terra cotta. They painted pictures of courtyards filled with tropical flowers, a great cage filled with “climbing plants and beautiful birds,” elaborate marble mosaics, a dining room “as large as an opera house” lit by stained-glass bay windows and electric light, views through orange groves and ornamental gardens, and a cascade, 450 feet long, adorned with fountains and statues.

The Ponce de Leon was called “a marvel in design and craft.” “Holy Moses,” gasped a train passenger when he first a saw it. “The sentiment, but not the words, is echoed by every passenger,” wrote a reporter who observed him. “The English language is incapable of furnishing words to properly express the sensations which come over one as he stands in the presence of this mighty monolithic reproduction of sixteenth century architecture,” wrote another.

Hotel Ponce de Leon, St. Augustine (Digital Commonwealth)

Flagler, with his near-limitless funds, had built a masterpiece. He had hired young architects John Carrère and Thomas Hastings, graduates of the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, who would later design the New York Public Library. They designed a symmetrical palace with domes, soaring turrets, balconies, and arcades surrounding lush, formal gardens and elaborate fountains. The concrete shone an off-white in bright sunshine and, at other times, reflected the light of the hour. Its ornamentation gleamed a bright red-orange. Inside, Flagler had furnished his palace with imported woods and hand-painted canvases. Thomas Edison himself installed the electric lighting.

But while Flagler’s project was assured of success, Smith’s was doomed from the start. His hotel, the Casa Monica, opened a few weeks later, in early February. Where Flagler’s hotel was elegant and stylish, Smith’s was eccentric. Where Flagler had built a Renaissance palace, Smith had built a brooding, Medieval fortress, its entryway modeled on Toledo’s city gate. Inside were courtyards filled with orange trees, walls covered in Valencia tiles, a magnificent sunroom, a shrine to Columbus, and Moorish-style halls with dancing, music, and “tableaus in costume appropriate to the surroundings.” They were spectacular, but, compared with the Ponce de Leon, the deliberate asymmetry, dark, winding hallways, heavy tapestries, and gas lighting seemed gloomy, meager, and outdated.

Hotel Casa Monica (later Cordova), St. Augustine, 1891 (Wikipedia Commons)

Before the season ended, Smith sold his hotel to Flagler, who renamed it the Cordova. Flagler eventually extended his railroad south, developing Palm Beach with Carrère and Hastings, reaching Miami, and in 1912, extending his railroad across the sea to Key West. Though St. Augustine’s short-lived primacy began to fade, Flagler still remains the father of modern Florida. Smith, its forgotten uncle, shared none of his fame or fortune.

Smith kept up his St. Augustine home and built a new Roman-style hotel, the Granada, next door. His wife, Laura, was famous for her Wednesday teas. Their departure each spring was understood to signal the season’s end. The Smiths’ son, George, helped found the annual tennis tournament, the Tropical Championship, and led visitors on boating trips across the wide Matanzas River to the black-and-white lighthouse on the sandy tip of Anastasia Island. Their daughter, Nina, wrote a book of fiction, Tales of St. Augustine, about the comings and goings of the Florida resort crowd. The family remained, for a while, fixtures of the winter resort in their curious Alhambra across from the Ponce de Leon. They hosted cotillions and banquets and appeared from time to time in the society pages of the Northern papers in columns with names like “Mid the Orange Groves.” But St. Augustine would forevermore be Flagler’s legacy, not Smith’s. He would have to set his sights elsewhere.

SIX

THE LAST DAYS OF POMPEII

On August 24, 1891, President Benjamin Harrison awoke in Saratoga Springs, at the luxurious Grand Union Hotel. After breakfast, Harrison, a brevet brigadier general during the Civil War, met up with an old army friend of his, Colonel Henry Clements, to speak of “old times and the days of the war.” They went for a drive together in an open-topped, horse-drawn carriage, and, at 10:30, finally returned to the private entrance of the Grand Union Hotel. Harrison enjoyed his morning “for his face was lit up,” wrote the New York Times, “with smiles when he stepped upon the veranda and unattended and almost unobserved, walked leisurely through the hotel office to the elevator and thence to his room.”

At four in the afternoon, the President arrived at the resort town’s strangest attraction, the House of Pansa, for a reception held in his honor by Mr. James S. T. Stranahan, the aging ex-Congressman from New York largely responsible for Prospect Park and Grand Army Plaza, and his wife. Invitations had been sent to nearly five hundred guests — governors, senators, mayors, clergymen, and “ladies and gentlemen of prominence” among them. Not a single one had fallen into “improper hands.” All the “best people,” including the “summer 500” were there to see the President, and Harrison was at the door to great every one of them. Having done his duty, at 4:30, he ducked inside to partake of Russian tea.

When the House of Pansa, more commonly called the Pompeia, had opened two years earlier, in August 1889, it had been the sensation of the summer season. Its builder, Franklin Webster Smith, had faithfully reconstructed the Roman villa featured in Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s 1834 blockbuster The Last Days of Pompeii. It sat on Broadway, like an ancient ruin just discovered intact and perfectly preserved beneath the Vesuvian ash.

House of Pansa (The Pompeia), 1900–1901 (Library of Congress)

Visitors entered the Pompeia through a vestibule, across a mosaic of a fierce dog warning “Cave Canem” and past busts of Cicero, Socrates, Plato, and Homer. Rich curtains hung from the ceiling, obscuring a view across a vast atrium with a lotus-filled, marble pool at its center. There were frescoes of birds chasing flies and “a string of fish, a small poker, a leg of mutton or ham, a spare-rib and the like.” The compound was illuminated with skylights that, when opened, allowed the free flow of Adirondack air. Fountains leapt, lending, with the marble floors, a “fragrant coolness.” Palms and other Mediterranean plants stood in urns throughout the space among white marble statues of Muses and Graces. On the building’s rooftop, guests promenaded beneath vine-covered trellises through an elevated garden.

But at its opening, gossip columnist Rosalind May was interested less in the building and more in the man, Smith, who had built it. “To me the man,” she wrote, “who within little more than a year could conceive and execute so great and interesting a work, was quite as much a study as the villa. He does not disappoint.” He was, she observed, a man of both brains and culture but also simple “charm of manner.” He was excited to speak with all his guests and showered them with “unaffected cordiality.” She called him “an educator in the highest sense of the term” and, though not strictly an architect himself, more accomplished than most professionals. “I should imagine his heart to be as warm as his mental faculties extended,” she said of him, “and thus without special effort he wins over everybody and imparts at least a touch of his own ardor.”

Smith had originally planned his Pompeia for St. Augustine. He even built a Roman-style shopping arcade there, beside the Villa Zorayda, which later became the Hotel Granada. When he built his Pompeia at Saratoga, he strived to make it as accurate as possible. When the Italian government refused to share plans for the actual House of Pansa with him, he studied models in the British Museum and the National Museum at Naples. When he was unable to find artists able to duplicate the Pompeiian style of painting, he dragged two Parisian salon artists with him to Pompeii with him to “catch the spirit of the decoration” and “transfer it to the new world.” From museum relics, he manufactured facsimiles of sofas, lanterns, and urns.

Hotel Granada (left) and Villa Zorayda (right), St. Augustine, 1890s (National Galleries of History and Art)

Saratoga was immediately smitten with its newest attraction. The American Architect called it “more successful as an educational curiosity than the celebrated Pompeiian Court at the Crystal Palace.” William Bradshaw, the editor of the Decorator and Furnisher (and author of The Goddess of Atvatabar, a hollow Earth novel), thought it a “poetical idea, fraught with great practical lessons to the age and the country.” It was men like Smith, he wrote, who would lead America out of the “artistic decline” of the Industrial Revolution and show the nation, “in all its material grandeur, the splendor of former ages.”

Unlike the frenzy of industry, in the face of the day’s “insane rush for wealth” and “total disregard of anything that can dignify the man himself,” Bradshaw wrote, the Pompeia imparted “the value of repose, and the health giving charm of stately surroundings.” Summoning memories of Babylon, Nineveh, Egypt, and India, Bradshaw lamented America’s “decline of sentiment, poetry, and imagination” wrought by industry and commercialism. It was men like Smith, he thought, who could save America from itself.

The only detraction came from Puck, America’s first successful humor magazine, which wrote, “A wealthy gentleman, who has a Moorish villa at St. Augustine, has just reproduced one of the houses of Pompeii at Saratoga. Next year he will build a Gomorrah cottage at Long Branch.”

House of Pansa (The Pompeia), 1900–1901 (Library of Congress)

During the summer seasons, Smith staged tableaux vivants for the resort crowd, where fashionable vacationers reenacted scenes from classical life and Bulwer-Lytton’s novel. In the winter dining room, guests reclined on sofas, about a table laid for a feast, with garlands atop their heads as “graceful girls” performed for them. Characters from the novel wandered about the villa’s columns in white, flowing tunics. The sweet melodies of Roman pipes and reeds echoed through the chambers like voices of yore.

Smith had other, grander plans for Saratoga. On the evening of July 8, 1893, he entertained the managers of all the Saratoga hotels. Months before, he had seen a floral festival in Santa Barbara. “My first impression, as I saw churches decorated with thousands of calla lilies, which grow in California hedge rows, and the masses of white roses embowering cottages and verandas, was that no place on earth could challenge Santa Barbara in floral display,” he told the New York Times. But remembering the “bright-colored flowers” and the “flowering shrubs, trailing foliage, and gorgeous leafage which emblazon the waysides and forests of the North,” he thought as beautiful as California might be, it couldn’t compare with upstate New York in late summer. And “in these days of rapid communication,” he added, “the luxurious products of Florida” — the yucca, pond lilies, tuberoses, and palmettos — could quickly be shipped north.

The morning of September 4, 1894, was beautiful. The air was cool and crisp, and the sun shone brightly, but subdued. Though the summer season had usually ended by now, as the air turned cooler and the leaves began to turn, thousands of vacationers still remained in Saratoga, and many more had just arrived by train. Bakers and milkmen made their rounds wearing leaf wreaths on their hats and flowers in their buttonholes. They decorated their vehicles with “flowers and gay flags.” Nursemaids walked their babies in carriages “gayly trimmed.”

Tens of thousands of people lined Broadway. They wore corsages and boutonnieres and garlands and carried great bouquets. Behind them, the buildings were bedecked in flowers and wreaths and garlands and greenery. Before them paraded a mile-long procession of flower-festooned bicycles, men and women atop horses covered in blooms, hundreds of floats “illustrative of historical incidents,” and carriages entirely concealed behind blossoms.

Floral Parade and Battle of Flowers Program, 1894 (New York Heritage)

Some floats were drawn by enormous oxen wearing floral garlands. Another, depicting the Pilgrims’ landing, was covered in asters, marigolds, and arborvitae and pulled by “milk-white” horses. The Sunday school float, pulled by eight white horses with white harnesses decorated with white immortelles and goldenrod, sported sunflowers and a sailboat plumed with white asters and white immortelles. Green vines hung from its sail. The sanitarium’s float was hidden behind a gradient of chrysanthemums fading from “golden yellow to creamy white.” A “Fairies’ Grotto” carried a six-foot long dragonfly and a fairy boat drawing water from a marsh of cattails and flowers. A small child, the fairy queen, sat atop the dragonfly’s back beneath a canopy of ferns and water lilies.

At Congress Spring Park, the entire parade retraced its steps down Broadway so that while one half of the parade was going, the other was coming. The final Battle of Flowers erupted. The paraders hurled vibrant flora at one another across Broadway. The onlookers lining the street threw their bouquets upon the passing revelers. They waved handkerchiefs and clapped loudly. The paraders in their floats and carriages hurled hydrangeas, roses, and carnations back at them. When the procession was over, Broadway was invisible beneath a million colorful blooms. “No more beautiful spectacle was ever witnessed here,” the Times wrote. Saratoga swelled with pride.

That evening, 5,000 men and women in fancy dress crowded into Convention Hall. Each woman wore an outfit that represented her favorite flower. Like a flower garden, the Hall was filled with flowers, cedar, spruce, and hemlock from the mountain forests. A floral queen entered with her “sister goddesses and satellites.” Thirty-four young women danced a “floral ballet” called the “dance of roses and butterflies.” Miss Ellen Beach Yaw, the coloratura soprano known popularly as “Lark Ellen” or the “California Nightingale” for her ability to hit the highest of notes and trill magnificently, sang the melancholy melody and bittersweet words of The Last Rose of Summer. The revelers danced into the early hours of the morning before retiring to their hotels and cottages.

Floral Ball, 1894 (New York Heritage)

The next few weeks included a tennis tournament and several conventions. By the end of the month, the last rose of summer finally drooped and faded, the ground hotels shuttered, and the season was ended as always. Smith proposed an annual industrial exhibit during the quiet winter months. He proposed a new Progress Park filled with pavilions, constructed of concrete, dedicated to “astronomy, electricity, chemistry, metallurgy, hydrostatics, pneumatic, &c., with distinct departments of natural science — geography, agriculture, navigation, transportation, sanitation, and education” linked by arcades and bazaars. He proposed an annual National Literary assembly. Its Executive Committee included notable women, like attorney Ellen Hardin Walworth and suffragist Ellen Henrotin. Patrons included governors and a certain Mark Twain.

The coming years brought more floral fêtes, more balls, and more conventions. In 1895, Smith chaired a committee advocating that Saratoga Springs, like Yellowstone, Yosemite, and Hot Springs, Arkansas, become a National Park. His plan required remodeling the entire center of town to create an enormous park to be “made a beauteous vista.” Broadway would be extended and lined with colonnades in the manner of Paris’s Rue de Rivoli with a balustrade above it offering respite from the crowds below. He would line the trees with trees to shade Parisian-style cafés. He called his scheme “A Greater Saratoga.”

Smith’s Proposed National Park, Saratoga Springs, 1895 (New York Times)

On August 24, 1891, after President Harrison drank his Russian tea, Smith delivered a lecture on Roman life. Harrison took Mrs. Stranahan by the arm, and, together, they promenaded about the ancient villa like Caesar and Cleopatra. They took in the frescoes, the sofas, the palms, and the bubbling fountain. They imagined the atmosphere of a town on the eve of destruction nineteen centuries before. Not even three decades earlier, it had taken the President of the United States to nullify the basest accusations of corruption against Smith. Now another President sat in his Roman villa, drinking his tea and imbibing his vision.

In the evening, Harrison returned to the Grand Union. He dined with friends, received ladies in the parlor, and, with the Stranahans, attended a charity ball at the United States Hotel. It had been, the Times wrote, a “very pleasant afternoon” indeed.

For Smith, though, it was only the beginning of greater things to come. He had built a Moorish palace in Florida and a Roman villa in New York. He had originated the idea for the reconstruction of La Rábida, the convent from which Columbus set sail for America, at the Chicago world’s fair. Now, he focused on Washington, the capital of the American empire. Visions of all the great past empires he had studied — of Europe, Africa, the Middle East, and Asia — flitted before him like fireflies, lighting up the night.

SEVEN

IN THE HALLS OF THE ANCIENTS

At six in the evening on December 28, 1896, two clerks at Julius Lansburgh’s Furniture and Carpet Company on Washington’s New York Avenue spotted the orange glow of flames near the building’s center and sounded the alarms. Lansburgh, sitting in his office, ordered his employees to save the company’s books, but there was no time. “The light from the flames made crimson silhouettes of all surrounding objects which had the advantage of height,” read the front page of the Washington Times the next morning. “It is safe to say that half the city saw the glittering gilt imitation of the orb of day on the Sun building, the white Moorish cupola on the home of the Riggs Insurance Company, and the great cross which surmounts Episcopal Church on G street.”

Spectators filled the surrounding streets and rooftops. Through the plate-glass windows, they could see “the setting crater of fire inside” bending iron beds and swallowing oak furniture. By seven o’clock, the fire was controlled. All that was left of Lansburgh’s building was a “smoldering heap of ruins.” The cause of the fire was ruled to be faulty electrical wires.

The site sat vacant for nearly a year. There was talk of a “commodious public hall” for fairs, bazaars, public meetings, and concerts, maybe even a “bicycle academy.” But, on January 5, 1898, the furniture store’s replacement was finally announced. “HALL OF THE ANCIENTS,” it said in the Post in bold, capital letters. The new attraction would contain “perfect reproductions of Egyptian, Assyrian, Grecian, Roman, and Saracenic architecture, manners, and life.” Just two blocks from the White House, its façade would form an exact replica of the Temple of Karnak, with columns 70 feet high and nearly a foot in diameter, every inch covered with figures and hieroglyphics.

A few months earlier, in the fall of 1896, Franklin Smith had turned 70. Looking back across the sweep of the decades, he reminisced on the greatest project he had ever envisioned and thought of the short time he had left in which to complete it. “The years of the writer must count few in their remand for activity, having already passed three score and ten,” he wrote the following year. “In impatience for the progress of what he believes a vast and practical national benefit,” he decided, that year, to “recommence its agitation.”

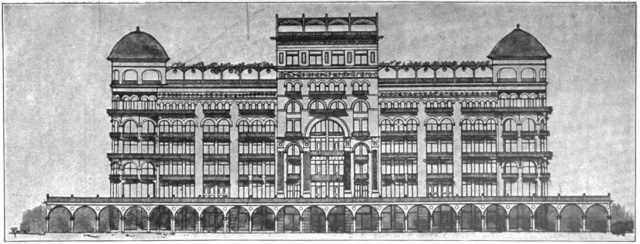

Smith called his vision the National Galleries of History and Art. Six years earlier, in December 1890, he had dazzled the world with an enormous watercolor installed over the mantelpiece of a the parlor of the Arlington Hotel. The Arlington was then one of the most opulent hotels in America and certainly the most luxurious in the capital. It occupied a vast structure behind an ornate Italianate façade of red brick and brownstone trim, beneath a grand Second Empire roofline punctuated with arched dormer windows. In summer, awnings shielded each room from the sun, and enormous American flags caught the breeze and fluttered from its roof. The hotel claimed an impeccable location across Lafayette Park from the White House, and its guestbook held the names of royalty, both of the old sort — Albert I, King of the Belgians; Dom Pedro II, Emperor of Brazil; Queen Kapiolani of Hawaii — and the new — J. P. Morgan, Andrew Carnegie, and Oscar Wilde. It was even rumored that the block in front of the hotel had been the first in the city to be paved with asphalt, so the clamor of horses and carriage wheels wouldn’t disturb the rest of the distinguished guests within. If ever there were a place to unveil a grand vision for Washington, it was in the parlors of the Arlington Hotel.

Smith’s plan for the National Galleries, 1891 (A Design and Prospectus for a National Gallery of History and Art at Washington)

Smith’s watercolor was the work of James Renwick. Renwick was one of the most accomplished architects of his day. Over his long career, he had built the Smithsonian Castle, St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York, the original Corcoran (now Renwick) Gallery, and the chapel at Georgetown’s Oak Hill Cemetery, where Washington’s elite were laid to rest. Renwick was also one of those who originally wintered in St. Augustine. He and Smith had become friends, and, after hearing of Smith’s plans for the capital, they became colleagues.

Renwick’s watercolor depicted, in stunning detail, a 200-acre dream city rising above the Potomac. Within its medieval walls and towers sat a maze of Assyrian palaces, Roman boulevards, and pavilions out of Egypt, Babylon, and Byzantium. Above the new city, on the hill where the old Naval Observatory then stood (and still stands), loomed three Grecian temples dedicated to American history. Smith called his city the National Galleries of History and Art and boasted it would harness “the grandeur of Rome” and surpass “all other previous constructions of mankind.” It could be built cheaply, too, he said, for only $5 million (around $125 million in 2018 dollars). Its low cost came from the material he would use to build it: concrete.

Smith published A Design and Prospectus for a National Gallery of History and Art at Washington, Bulletin No. One of the Offices of the Propaganda for the National Gallery. He sent it to every member of Congress, promising those who purchased an additional 25 copies would be added to a list of Propagandists.

Two towers, capped with pyramids like the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, guarded the district’s entrance. Two rounded arcades, like outstretched hands, cradled an oblong pool. A pathway led visitors across the pool on a causeway between two lines of columns capped with statues. Through a pair of Roman-style triumphal gates, dedicated to Lincoln and Washington, rose a flight of stairs up to the American Acropolis. Its three Grecian temples would define the capital’s western skyline as a counterpart to the Capitol Dome to the east: “the one expressive of the highest legislative wisdom, the other of the resultant intellectual development of a nation.”

Along the central Via Sacra stood a Roman Court and Theatre, reproducing the ancient Roman sewer system, the Roman catacombs, the Porta Maggiore, the lava-covered ruins of Pompeii, a Roman villa, and full-size replicas of Trajan’s Column and the Pantheon. A Greek Court housed an agora, the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, and the Caryatids of the Athenian Acropolis. Medieval and Renaissance Courts contained the homes of Martin Luther, Peter the Great, Shakespeare, Mozart, and Michelangelo; the cell of Marie Antoinette; convent cloisters; and the baroque arches, soaring domes, and white bell towers of San Salute in Venice. A Moorish Court, entered through Toledo’s Puerto del Sol, contained the Córdoba mosque and the Alhambra. An Indian Court contained the Taj Mahal. Assyrian, Byzantine, and Persian Courts contained the throne room of Nineveh and the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople.

Outside the city gates, an Avenue of Sphinxes led from the base of the Washington Monument, past the Temple of Medinet-Habou at Thebes, through a line of lotus-capped columns, to a Gothic bridge stretching across the river to Arlington. Beside this path sat the three pyramids of Giza illuminated from within by electric light. “Imagination may picture glowingly to the eye of the mind,” Smith wrote, “this vast pile, darkening by its stately mass the setting sun, whose rays gleam upon the rippling river through the majestic portals, while Eastward, they ‘linger and play upon the summit’ that inspires faith in a long future for the work of Washington.”

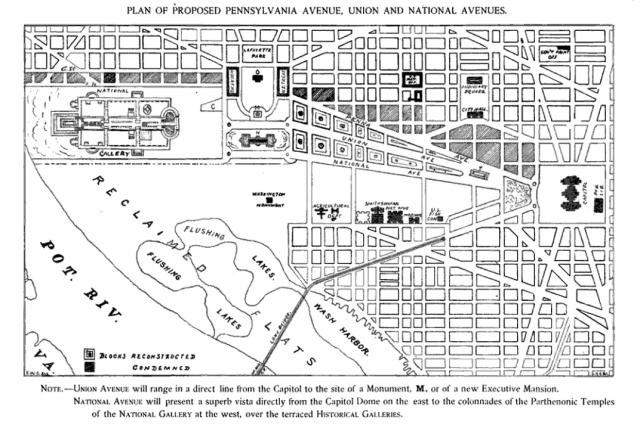

Smith dreamed, too, of redeeming the surrounding capital, as “Baron” Georges-Eugène Haussmann had done for Paris just decades earlier. He dreamed of “Haussmanizing” the Murder Bay neighborhood (today’s Federal Triangle), which had long been considered a blight and a hotbed for crime and vice. At its center sat the reviled, monolithic tower of the central Post Office (today’s Trump Hotel), built of gray stone in the by-then unstylish Romanesque Revival style. Smith imagined disguising it behind a classical façade and scavenging its tower to build a replica of the fourteenth-century Rheinstein castle along the Potomac. He would remove the Central Market from the site of today’s Archives and remove the old Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station (site of President James Garfield’s 1881 assassination) from the site of today’s National Gallery, whose tracks snaked south across the parkland of the Mall. Smith imagined new boulevards spreading from the Capitol like spokes of a wheel: Union Avenue, running from the Capitol to the South Lawn of the White House, and National Avenue, from the Capitol to the National Galleries.

Smith’s proposal for central Washington, 1891 (A Design and Prospectus for a National Gallery of History and Art at Washington)

Smith never intended his document to simply lay out a dream. He filled it with discussions of financing, cost estimates, a treatise on the cost-saving virtues of concrete, and the names and accolades of his well-known supporters. In Washington, he petitioned Congress for land — initially the site of the old Naval Observatory, then the site of the Old Soldiers’ Home — and $200,000, the amount he figured he was owed for being the “Dreyfus of the civil war.”

While some Congressmen joked of “Smith’s Park,” the press was enthusiastic. “Few words, lacking adjectives and color” could convey “an idea of the great beauty” of Smith’s plan, the Washington Post wrote, and the New York Times thought its benefits “self-evident” and its construction “due to ourselves as a nation, and to our posterity.”

Smith appealed to patriotism, comparing the young, shabby American capital with the old imperial capitals of Europe, and the line of argument seemed to work. William Drysdale, writing after his visit to St. Augustine, shamed his countrymen for being, in spite of their wealth, “the only great country which has done nothing as a nation in acknowledgment of the claims of art.” The American ambassador in Athens, the heart of antiquity, urged America to realize Smith’s vision, in order to become “the intellectual and moral guide of the nations.” The benefactor of New York’s Metropolitan Museum thought the idea not only “a hundred years ahead of its time” but practical and feasible. Several senators immediately lent their support.

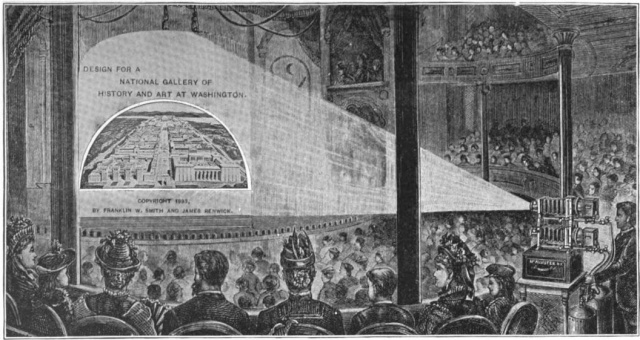

As the plan garnered press, Smith set out on a lecture tour. He traveled to Boston, Brooklyn, and Philadelphia. “Every one who heard the eloquent speaker,” the Philadelphia Times reported, “became enthusiastic over the grand project and was carried away with the beauty of the plans.” In New York, he spoke with J. P. Morgan, and, in Washington, he spoke before the congressmen living at the Elsmere Hotel. He traveled to California, speaking before crowds in Pasadena and San Francisco. The Los Angeles Times declared his project “the most magnificent architectural conception that has ever been formulated.”

Smith presenting his scheme, 1890s (National Galleries of History and Art)

But, like the Chicago Bazaar of the Nations was dashed by the Panic of 1873, the Panic of 1893, far worse than its predecessor, overtook Smith’s National Galleries. Hundreds of banks closed, tens of thousands of businesses failed, railroads went bankrupt, and unemployment soared to nearly 25% in some major cities. It seemed hardly the time to build a fantasy city of ancient temples in the nation’s capital, no matter its benefits.

For three years, Smith wintered in his Alhambra in St. Augustine and summered at his Pompeiian villa in Saratoga. But Smith, by now nearly 70, was only so patient.

In 1896, he returned to Washington. He organized the National Galleries Company, and his old friend S. W. Woodward, co-owner of the successful Woodward & Lothrop department store, became its Vice-President. Two prominent bankers (and, for a short while, a real estate magnate) joined them in the enterprise. They acquired the old offices of the Congressional Globe at 339 Pennsylvania Avenue, within sight of the Capitol.

Smith took up residence at the Elsmere Hotel on H Street, just off New York Avenue. The Elsmere sat just around the corner from the ruins of Lansburgh’s store. Smith must have passed the vacant site each day as he traveled to his office. Through the skeletal remains of tortured bed frames and wardrobes turned to ash, Smith must have seen the hazy outline of the Temple of Karnak rising above the “smoldering heap of ruins.” Just beyond, hazier still, he saw a city rising on a hill. Through medieval Spanish gates, a road ran across a lake through Roman temples, Moorish castles, and Assyrian palaces. A broad flight of stairs led up to a Grecian acropolis. It all seemed so beautiful, so ethereal, and, for the first time, nearly within reach.

A few months later, in the spring of 1897, Smith published an illustrated brochure to supplement the original 1891 prospectus. It proposed the Halls of the Ancients, and its cover carried the image of a reimagined Karnak crawling with red and blue hieroglyphics, lotus-capped columns, and the symbol of a winged sun. The Halls of the Ancient would be, Smith hoped, the strongest argument yet for his National Galleries. “I intend this building and this exhibition to serve as an argument for something else,” he said later. “I want Congress to appropriate enough money to build on the banks of the Potomac a series of gardens and buildings to be known as the National Galleries of Art and History, which shall be unsurpassed by anything in the world. If my scheme could be carried out — and I sincerely believe that it will be some day — then the Capital of this nation would become the world’s center of art, literature and learning.” He vowed to “devote all my energies in the future to seeing that this magnificent scheme is brought to a fulfillment, and in case I do not live to see it, I shall leave behind me a most eloquent argument in the shape of the Halls of the Ancients.”

From National Galleries of History and Art, 1900

As he had years earlier, Smith sent his prospectus to prominent people. Echoing his treatise, The Hard Times, of two decades earlier, he spoke of the dangers of “over-production, displacing labor of the working classes,” of the limitless leisure time of an impending six-hour workday, and a growing “discontent with increasing disparity to vast wealth of the few with the struggle for means of living with many.” He spoke of Communism as the problem and public institutions as the solution, the means by which to turn leisure time from “danger” to “benefaction.” He concluded, “Now if the rich will let their worth flow out for such stimulus to patriotic pride, for such material for thought and study, for such admiration of their capital by our countrymen, the hearts of the people will flow together in good-will.”

The Secretary of the Navy, who held the office of the man who had conspired against Smith decades before, lent his support. Quite a few senators appealed to America’s wealthy, arguing the amount of money required to complete it “is insignificant comparatively with the volume of national wealth.” Among them, Smith found his political patron: Senator George Frisbie Hoar of Massachusetts.

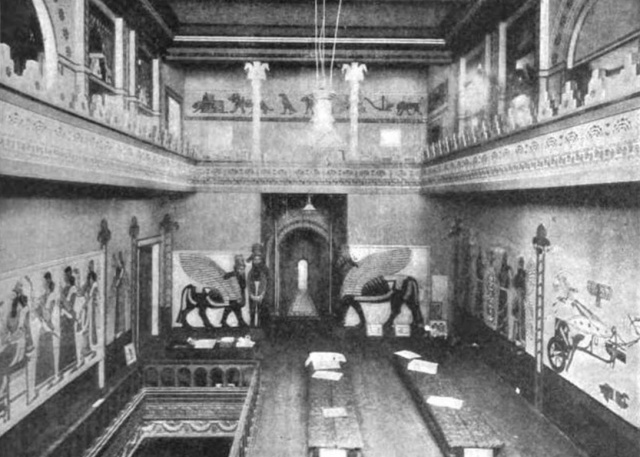

Within a year, Smith had quietly acquired the old site of Lansburgh’s store. Construction was hushed. Smith supervised the workers himself, allowing no one inside except by his invitation. In July, he completed the first halls, depicting Egypt and Assyria, in time to host the National Education Association’s annual convention. He produced a special pamphlet, installed paintings and engravings, displayed a mummy purchased by Woodward in Cairo, and personally led tours of the educators through his curious exhibits. “The building in which the exhibit was held will, in the course of a few years,” the School Journal reported, “doubtless, be one of the sights of Washington.”

By November 1896, the concrete façade, perhaps the first in Washington, was mostly complete. It was then “ugly and commonplacely grotesque,” one Post reporter recalled, but he spoke of the marvelous ornamentation that would soon follow. The reporter described the façade’s immense towers, and the Egyptian throne room beyond with its twelve enormous columns rising several stories high. He described a high-ceilinged Roman atrium paved with colorful tiles with a marble pool at its center fed by spouts of water emerging from lions’ heads. Scattered about were tables, chairs, couches, musical instruments, and statues of the Muses reproduced from Roman originals. Smith led the reporter through the rooms depicting the Alhambra, Persia, and an Assyrian throne room, its walls and doors painted deep blue and rich green, guarded by a five-legged lion.

Assyrian Throne Room, Halls of the Ancients, about 1900 (National Galleries of History and Art)

Washington eagerly awaited the opening of its newest attraction. On Christmas Day, an enormous, colorful painting of the Temple of Karnak finally appeared over the façade. January came and went. Finally, on February 3, 1899, an advertisement appeared in the Amusements section of the Evening Star. The Halls of the Ancients would be open to the public on Monday, February 6, at nine in the morning. Visitors could expect to see the Egyptian portal, with its 70-foot columns, and the Hall of Columns. They would see a facsimile of the famous Book of the Dead and an ancient tomb, an Assyrian Throne Room, “gorgeous in blue and gold” with the four “colossal human-headed bulls” from the palace of Sennacherib, who himself would sit upon the Throne of Xerxes at the halls’ center. There would be a Roman house, too, and a Lecture Hall in the Persian style. There would be a Saracenic Hall and an Art Gallery, even a Taberna where visitors could purchase “copies of superb ancient vases and interesting souvenirs.” Mr. Franklin W. Smith, curator, would speak three times daily, at eleven in the morning, four in the afternoon, and 8:30 evenings.

But life frequently played cruel jokes on Smith. During the night of Sunday, February 5, 1899, hours before the opening of the Halls of the Ancients, seven-and-a-half inches of snow fell as Washington slept. The next morning, the capital was covered with white. Men shoveled the major intersections, and trains were unable to climb the hills. Children sledded down Thirteenth Street by the Halls of the Ancients. They threw snowballs and built snowmen and forts in the long shadow of the Temple of Karnak.

Assyrian Throne Room, Halls of the Ancients, about 1900 (National Galleries of History and Art)

It continued to snow through February 6, and, by the time the city awoke on February 7, another foot had fallen. It was “the heaviest recorded in so short a time in many years.” Snow banks lined the streets, and horse-drawn carriages struggled to move about the city. Sleighs were dragged out from sheds, and the streets filled with the sound of their bells. The papers recounted the story of a “jolly fat man whose sleigh overturned” and the travails of the city’s Chinese community then planning its New Year’s celebrations. The next several days brought the Great Blizzard of 1899, dumping twenty inches on the city. Smith later recalled the “unprecedented” storm that “held Washington in Arctic environment for thirty days.”

Little by little, though, reports of Smith’s attraction began to appear in national journals and newspapers across the country. High school students visited. Little by little, Smith’s vision began to appear as if it could become a reality. By now, though, Smith was nearly 73 years old. He had worked tirelessly to realize his dream, placing great strain not only on his relationships with his wife and children but on his health. He was left, he wrote, “utterly prostrated.” In May, he slipped out of the country, alone, to recuperate at Carlsbad near Prague, visions of a new Washington dancing in his head.

EIGHT

THE AGGRANDIZEMENT OF WASHINGTON

In 1800, Washington became the new capital of a young country. By 1900, it had become the pride of an empire. Over the intervening century, America had grown from a collection of breakaway colonies to a transcontinental power, the world’s wealthiest nation and one of its most populous. During this single century, the capital grew from a scattering of settlements surrounded by farmland to a city of nearly 300,000. Though the city had been master-planned by Pierre L’Enfant, it had developed haphazardly. There was not yet a Jefferson or Lincoln Memorial, a Union Station, a National Gallery, Supreme Court, or National Archives. As Paris and Berlin reshaped themselves through monumental building projects, Americans, Franklin Smith among them, compared their capital unfavorably with the great cities of Europe and agitated for change.

A movement to transform Washington was not entirely new. Since at least the 1850s, there had been plans to replace the White House. In 1857, one paper said matter-of-factly “there can be little doubt that the erection of a new Presidential mansion will be one of the measures that will receive the favorable action of the next Congress.” In 1866 and 1873, Congress ordered surveys of new locations on higher ground. In the 1880s, a senator proposed building a new White House directly south of the old one, identical in form and connected to it by a broad, central corridor. And in 1889, almost as soon as her husband took the oath of office, Caroline Harrison agitated for a new Executive Mansion. The following year, she released plans showing two statuary halls extending east and west from the existing residence, curving around to two parallel halls, one public and one official, and a line of conservatories. Within the courtyard stood a “grand allegorical fountain” honoring “the discovery of America in 1492, laying of the corner-stone of the Executive Mansion in 1792, and the triumph of free institutions in 1892.” At its center, colored lights illuminated a statue of Columbus.

Harrison and Owen’s plan for the White House, 1889 (The Outlook)

Or take the Memorial Bridge. The idea for it arose in the wake of Ulysses S. Grant’s death, when the Washington Critic proposed a bridge linking North and South in honor of the late president. The Baltimore Bulletin suggested that the bridge, at its center, should hold twin statues of Grant and Lee, and that each of the states could place “dead generals of reputation” on pedestals along its span. One artist suggested a stone bridge with one enormous arch spanning the whole, wide river. The Commissioners of the District Columbia favored a Gothic bridge, built of granite and bookended by four towers 250 feet tall from some great château, two for the North and two for the South. Each Congress saw bills for the bridge, and in each Congress they failed.